Vision Project: The Politics of a "New Economy"

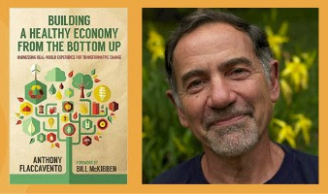

Anthony Flaccavento’s run for Congress in Virginia’s

9th district suggests a new way forward for progressive politics. His issue platform incorporates many of the ideas he puts forward in his book, Building a Healthy Economy from the Bottom

Up: Harnessing Real-World Experience for Transformative Change. A farmer

from rural western Virginia, he presents a modern articulation of communal and agrarian

values that emphasizes community control of the economy and a return to respect

for the land as the ecological base for society. He adopts a pro-business yet

anti-corporate stance, emphasizing the need to “level the playing field for

workers, local businesses and the community banks that lend to them” while also

“reinvigorat[ing] anti-trust laws to reverse the extraordinary concentration of

power held by a handful of giant corporations.” Focusing on health care,

education, energy, and agricultural policy – issues important to rural voters –

he calls for Medicare for All, free community college for all, and a “Marshall

Plan” for Appalachia based on a just transition away from coal, among other

progressive ideas.

Flaccavento’s platform

is not without its limitations. For instance, he does not discuss issues of

particular importance to people of color, immigrants, or the LGBTQ community,

including criminal justice and immigration reform and non-discrimination legislation.

He also does not discuss housing or transportation policy, which is

particularly important to urban voters. He also makes no mention of foreign

policy, nor of the need to protect civil liberties. However, such omissions do

not necessarily mean he doesn’t have a progressive stance on these issues.

Instead, he is simply not emphasizing them in a 90% white, pro-Trump rural

district. Importantly, he does not take a conservative stance on any of the

issues he does take a position on. In

other words, while his platform may not be comprehensive, it is noncompromising.

He takes explicit pro-choice and pro-gun control positions, which is refreshing

to see coming from a Democrat running in a conservative area.

Flaccavento’s book and platform are part of a broader

trend of economists and activists, including Gar Alperovitz, Marjorie Kelly, David

Korten, Bill McKibben, and Richard Wolff, who advocate for what has been dubbed

the “New Economy” – the transition to a cooperative economic system. Such a

system relies on neither markets nor states, although it does not completely

eschew either. Instead, it is based on constructing new economic institutions

that promote direct democratic control by workers and communities, including

cooperatives, worker-owned and self-directed enterprises, locally owned small

businesses, and publicly owned enterprises. Such a system aligns with the

thinking of Elinor Ostrom, the first (and to date only) woman to win the Nobel

Prize for economics, whose Nobel lecture was titled “Beyond Markets and States”.

Best known for her work analyzing the commons, Ostrom advocated for bottom-up,

democratized control of the economy, as opposed to top-down private or state

management.

Flaccavento’s platform would go a long way toward

addressing the issues laid out by Steven Stoll in Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia. Employing a critique of

capitalism similar to that of Karl Polanyi, Stoll describes the rise of

industrial capitalism through the lens of the Appalachian agrarian. He

emphasizes that throughout history humans have lived subsistence lifestyles

based on household economies. Private ownership of property, by contrast, is a

very recent development, one which led to enclosure of the commons, destruction

of the subsistence economy, and mass dislocation of whole societies – a process

which continues to this day. Like Polanyi, Stoll argues that capitalism was not

inevitable, but came together due to the conscious commodification of land,

labor, and money. For his part, Polanyi puts forward the idea that a

market-based system is not the natural organization of society, and like

private property is a recent development in human history. He argues that the creation

and maintenance of a market-based system has produced unsustainable social dislocation.

(Psychologist Bruce Alexander in part used Polanyi’s analysis to develop his “dislocation

theory of addiction” – for which the opioid epidemic across Appalachia

unfortunately provides further evidence.) Such dislocation in turn has produced

a “countermovement” designed to protect society from the effects of the

market-based system.

This analysis of capitalism by Stoll and Polanyi serves

as a particularly useful framework for understanding the development of

neoliberalism and the increasing rejection of it from both Right and Left in

recent years. In the 2016 election, this manifested itself in the form of support

for the presidential campaigns of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Flaccavento’s

run for Congress represents another rejection of neoliberalism, as he seeks to end

both the limitless extraction of the Earth’s resources and the exploitation of

workers and the communities they work and live in. Furthermore, Flaccavento

wants to start to rebuild the household economy referenced by Stoll, and make sweeping

changes to our current economic system as a whole to make it based less on

generating profit and more on building community and protecting the ecological

base – in other words, decommoditizing land,

labor, and money.

I think that what Flaccavento and others argue for is

largely missing from the Left’s mainstream narrative and agenda, which I feel limits

the political potential of the Left. From a public policy perspective, promoting

alternative institutions would help build relocalized, more sustainable

economies. It would also help to rebuild communities and their social capital

and begin to reverse the dislocation caused by capitalism, especially its

neoliberal manifestation. Politically speaking, advocating for alternative institutions

would help provide a path forward for the growing numbers of people who are

skeptical of capitalism and open to social democratic or even socialistic

ideas. While current Left thinking seems to focus mostly on “countervailing” or

“leveraged” power (i.e. taxation, regulation, and unionization) – which assumes

that corporations will remain the dominant economic institution – I prefer that

workers take power directly. Additionally, because such solutions do not typically

rely on the government, they can have broader appeal than other programs more

reliant on the state. It would also help promote a narrative that begins to

shift from thinking of government as some separate entity known as “the state”

and toward actually being made up of “the body of the people”.

I see enormous political potential for this public

policy platform, particularly as it relates to the Democratic Party. It is no

secret that Democrats have struggled mightily to win votes outside of urban

areas and college towns. Looking at a precinct level map of the 2016

presidential election results displays just how stark the situation is. Of

course, Democrats can and do win in rural communities of color, including in

the Black Belt of the South and in the Latino and Native areas of the West.

Nonetheless, the Democratic strategy, vividly on display during Hillary Clinton’s

campaign, has been to court college-educated suburbanites. This has led to

alienation of rural and small town voters as well as depressed turnout in the

inner cities. If the Democrats want to retake power at the state and federal

levels, they’ll need to build a multiracial, class-based urban-rural coalition.

To do so, Democrats need to move away from the neoliberal,

corporate-based “blue state” economic development model described by Thomas

Frank, and instead adopt the bottom-up, local community-based one proposed by

Flaccavento and others. In New York this includes rejecting the economic

development model of Governor Andrew Cuomo, which is based on providing

subsidies, tax breaks, and other incentives in an attempt to bring in large

firms and enterprises from elsewhere (e.g. his failed STARTUP-NY plan). Doing

so could help to bridge the so-called “urban-rural divide” that has dominated New

York State politics. To that end, I am encouraged by gubernatorial candidate Cynthia

Nixon’s recent tweet: “It’s time for a smarter, bottom-up approach to economic

development in New York state. The community must be included in the decision

making process and all projects should meet local needs and serve local

populations.” Although not quite as comprehensive as Flaccavento’s vision, it is

still refreshing to hear a Democratic politician employ such rhetoric. Let’s

hope that more politicians – Democratic or otherwise – start to take a similar

approach.

Further

Reading:

- Alexander, Bruce K. The Globalization of Addiction: A Study in Poverty of the Spirit, 2008.

- Alperovitz, Gar. America beyond Capitalism: Reclaiming Our Wealth, Our Liberty, & Our Democracy, 2011.

- Alperovitz, Gar. What Then Must We Do? Straight Talk about the Next American Revolution, 2013.

- Flaccavento, Anthony. Building a Healthy Economy from the Bottom Up: Harnessing Real-World Experience for Transformative Change, 2016.

- Frank, Thomas. Listen Liberal: Whatever Happened to the Party of the People?, 2016.

- Kelly, Marjorie. Owning our Future: The Emerging Ownership Revolution, 2012.

- Korten, David C. The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, 2006.

- McKibben, Bill. Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, 2007.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2001.

- Stoll, Steven. Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia, 2017.

- Wall, Derek. Elinor Ostrom’s Rules for Radicals: Cooperative Alternatives beyond Markets and States, 2017

- Wolf, Richard. Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism, 2012.